The Greater a Community’s Loss in Common Ground, The Greater the Resulting Gain in Violence

By Jean Pierre Ndagijimana, PTR African Communities Wellbeing Coordinator

On September 21st of each year, the United Nations observes the International Day of Peace. This  day marks the UN’s declared 24 hours of cease-fire for everyone on Earth to experience the ideals of peace, to breathe freely, and to find a gap of calm. The international theme for the 2020 Peace Day was, “Shaping Peace Together.” As the world celebrated “peace” amidst collective accumulated stress, the pandemic has seemed to remind us that while there has never been a good time to turn against each other, now seems an especially senseless moment to do so. The pandemic has challenged our existing understanding of what “peace” really means, and who or what our real enemy is or can be. The blurriness of “peace” in this particular time invited us to use this day as an opportunity to use what we have: virtual gathering, to interrogate and expand our understanding of the concept of peace, and to arm ourselves with newer tools, as well as those we already had but never tapped into or which we had ignored, to create peace in our lives, our homes, and in our communities.

day marks the UN’s declared 24 hours of cease-fire for everyone on Earth to experience the ideals of peace, to breathe freely, and to find a gap of calm. The international theme for the 2020 Peace Day was, “Shaping Peace Together.” As the world celebrated “peace” amidst collective accumulated stress, the pandemic has seemed to remind us that while there has never been a good time to turn against each other, now seems an especially senseless moment to do so. The pandemic has challenged our existing understanding of what “peace” really means, and who or what our real enemy is or can be. The blurriness of “peace” in this particular time invited us to use this day as an opportunity to use what we have: virtual gathering, to interrogate and expand our understanding of the concept of peace, and to arm ourselves with newer tools, as well as those we already had but never tapped into or which we had ignored, to create peace in our lives, our homes, and in our communities.

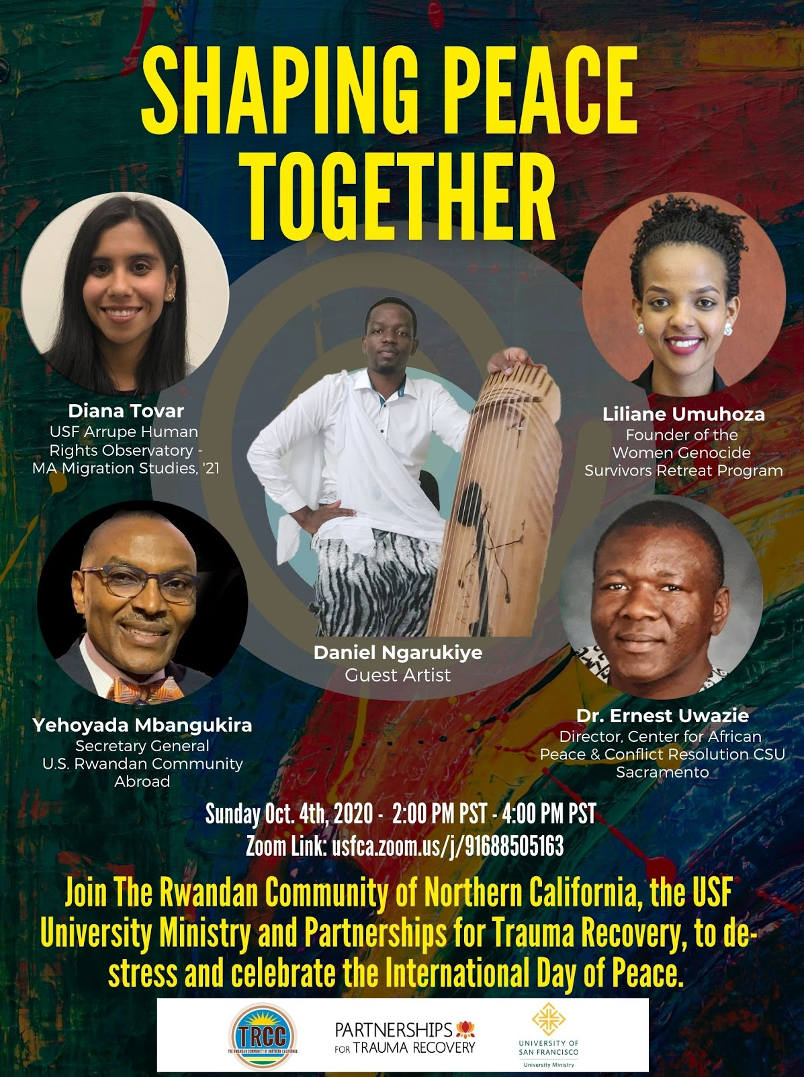

On October 4th, 2020, the Rwandan Community of Northern California (TRCC) together with the African Communities Program at Partnerships for Trauma Recovery (PTR), and the University Ministry at the University of San Francisco, joined to co-host the International Day of Peace. Hosting an event called “celebrating peace” could in some ways feel inconsiderate to many people who have been experiencing heightened stress from the layers of pandemics we are all experiencing similarly and differently. Given the complexities of the current moment, we expanded the universal theme. What follows is sharing of highlights from our discussion around de-stressing and shaping peace together.

As many of us engage in the digital world and try to creatively bring our communities together, there are enormous self-doubts: Will people really want to join the Zoom Meeting? What if we spend all our energy and people do not show up? What if only one person comes? What if the materials we plan to use do not work? Will we ask people to turn on their cameras? Is that even okay to ask? A discussion on whether we send out a link or a Zoom ID may take hours because there are so many unknowns as we all engage in trial and errors to adapt to find some equilibrium in a trembling world. After many weeks questioning our strategies and capacities to host the event, we were surprised to see so many people joining the call.

The event opened with words from Angélica Nohemi Quiñónez, the Interim Director of the University Ministry at the University of San Francisco (USF), who welcomed all of us and emphasized the importance of this space as one for sharing stories, different perspectives, opinions, and ideas. Tizita Tekletsadik, PTR’s African Communities Program Manager, followed, acknowledging the stress associated with the pandemic, and invited Yehoyada Mbangukira, the US Rwandan Community Abroad’s Secretary-General, who welcomed participants on the behalf of TRCC and moderated the conversations. Our guest artists, Daniel Ngarukiye, Inzora Benoit, and Bosco Intore, played their part: they entertained the heart with some soothing music and playing Inānga, a Rwandan and Burundian traditional music instrument. Beside offering participants with the opportunity to regulate stress through our guest artists, understanding the concept of peace especially today, and what we need to achieve it, was at the heart of the conversation.

Diana Tovar, a Master’s Student in Migration Studies and a member of the USF Arrupe Human Rights Observatory, was one of our panelists. Ms. Tovar rooted her perspectives in experience in Colombia. When asked to define peace in the current moment, Ms. Tovar said, “Peace is a social construct, it requires recognizing that others’ pains are my pains too.” Currently, “Peace is any act of kindness, generosity, a smile, love, understanding, empathy, and putting aside what divides us,” she added. “Peace is empathy and a continuous commitment to our own and others’ wellbeing.” She challenged the dominant notion of equating peace with the mere signing of peace agreements. For Ms. Tovar, peace is a path and a goal, and we achieve it only when individuals and the larger society recognize that something is wrong and they are willing to do their part to change what does not seem right. It is in that regard that she reminded the audience to use their privileges not just to help others but to build bridges between our communities. She warned the audience about the path some take deepening the gaps of inequality and vulnerability rather than healing the divides. She therefore condemned indifferences to racial injustices. According to Ms. Tovar, for our communities to achieve peace, we need to engage collectively. This is because, in order for us to exist as individuals, we are required to first exist as a society. She invited us to welcome and tolerate the beauty of our differences, and to respect each other.

Another panelist, Liliane Umuhoza, Founder of the Women Genocide Survivors Retreat Program, reflected on her personal experience of surviving the genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda. She defined peace as fulfilling the empty promise of “Never Again” that failed to prevent the genocidal tragedies in 1994 after many other “Never Again” statements that had preceded these atrocities. Drawing from her personal and collective experiences, Ms. Umuhoza chose to use the words ‘peace’ and ‘equality’ interchangeably; lack of equality means lack of peace. For her, peace means access to food, to shelter, and to other basic needs. “When we think about ‘peace’ we should not just think of UN, but Us,” she shared. “Peace is not the absence of war, and it is important that we continue redefining the term,” she added. For Ms. Umuhoza, there is no peace when there is racial injustice, there is no peace when a pandemic affects people differently because of who they are as a community. She emphasized that when thinking about ‘peace’ during the Coronavirus pandemic, mental health needed to be considered. In her words, “When your mind is not stable, it affects everything around you.” She called this type of peace ‘psychological safety,’ where people can feel free to share their stories and feel heard. According to Ms. Umuhoza, because of the ongoing pandemic and racial injustices, mental health support is becoming a basic need. She believes that the public, collectively, has the power to shape peace, and she invited the public to treat peace as their everyday businesses. That means, “Stepping outside our comfort zones and interacting with people who are different from us, not seeing the difference as a problem or a threat, but cherishing the diversity,” she added. We have the power to shape peace, and doing so requires a collective effort.

Dr. Ernest Uwazie, another panelist, is a Professor and the Director for the Center for the African Peace and Conflict Resolution at CSU Sacramento. For Dr. Uwazie, “Everyone deserves peace, and peace may look different from place to place and from time to time.” Dr. Uwazie spoke of the idea of Ubuntu – the concept that ‘I Am Because We Are.’ He built on an Ubuntu Afrocentric lens to define peace – not to romanticize the continent, but to recognize the African peace heroes who have been victimized, and for all of us to be humble in our own failings and to learn from our wrongs. Quoting Mandela of South Africa, he said, “Peace is not just the absence of conflict, peace is the creation of the environment where all can flourish regardless of race, color, religion, gender, class, or any other marker of social difference.” Summarizing this through his own lens, Dr. Uwazie said, “Peace is a satisfaction of one’s interests of justice, substantive justice.” He explained that peace is recognizing that every human being is worthy of recognition, worthy of fair treatment, free from eminent and remote threats; it is when all of us can dream as far as we can. Recognizing the increase of domestic violence during the pandemic, he said, “Do no more harm.” He reminded the audience that every human being has the potential to do good, and he invited us to be resilient, reconcilable, and suggested that we condemn not the person but the bad. He encouraged everyone to be willing to serve the public, and, “If there is no organization you can join, create one!” he said. To start, he invited us to be educated about the issues with which we are dealing. He also suggested that we do the work in the spirit of Ubuntu. For the professor, while we tend to magnify our differences and risk losing the sense of our core similarities, there are many more things that we have in common than the differences we think exist, and those commonalities could serve as bridges to build our relationships and stronger communities.

What is your own most recent definition of peace?

As people who were interested in attending RSVPed online before the event, they were asked to participate in “shaping peace together” by sharing their own current definitions of peace. Forty nine (49) of the participants shared their views of what peace means in the current moment. Below are a few of them to conclude with:

- Peace means accessing the basic needs that are required to live.

- Peace today means living in a country that is protective of its own people addressing the Coronavirus pandemic.

- There is what we call peace because there is no war, and there is inner peace and both can be different.

- Peace is the ability to remain resilient, happy, and self-loving, even when I have problems, there is hope that I will overcome them.

- Peace is when one is not threatened in the present moment and they are not concerned about their future living conditions

- Entre los individuos, como entre las naciones, el respeto al derecho ajeno es la paz.” — Benito Juárez / Translation: Among individuals, as among nations, respect for the rights of others is peace.

- Inner peace, being in harmony with my own self and thoughts, as well as outer, wishing but also working towards peace – at local and global levels

- Having Christ in my heart is peace to me.

- Kuri njye numva amahoro ari igihe umuntu aba adafite ibimuhungabanya muri we no hanze ye.

- Peace Is a continuous process of awareness and commitment to one’s own well-being and the well-being of others. It begins with recognizing that something is wrong and making the effort to understand why it is wrong. Peace ends up being a social construct.

- I am at peace when I am able to do something for someone in need.

- Peace is understanding that we are all in this together. To know, to listen, to care, and to understand each other.

- Peace is about selflessness, love, empathy, justice.

- Feeling safe at home and outside. When everyone has the same human rights and dignity respected.

- Peace means leaving America to be amongst my people.

- Respect for others rights.

When closing the conversations, Mr. Yehoyada, who moderated the panel, shared his major takeaway: shaping peace together is within our power. This happens by being responsible, resilient, not being indifferent when others are experiencing injustices, and understanding that we are all in this together, because there is no community made up of one person. With that, according to Mr. Yehoyada, the panelists gave us tools we can employ to shape peace together. “We can all, indeed, shape peace together,” he concluded.

The success of this event is a result of a collective commitment. I would like to thank all the contributors: the participants in the event for their active participation, our speakers, moderator, guest artists, the organizing team, and the co-hosting organizations. The Greater a Community’s Loss in Common Ground, the Greater the Resulting Gain in Violence. We can, collectively, shape peace together, and we are shaping it.